Indigenous rights, film and empowerment

LifeMosaic at work (Photo: LifeMosaic)

I met Serge Marti at a Practitioner and Research Mixer organised by the School of Geosciences at the University of Edinburgh last November. He very kindly agreed to answer some questions regarding the experiences he has had during his career and the challenges faced by indigenous peoples around the world.

Serge Marti is the executive director of LifeMosaic. He is an anthropologist and forester, fluent in 5 languages, with over 20 years experience working with indigenous and farming communities in Latin America and South East Asia; helping facilitate the set up of several community-led organisations; and developing methodologies for community empowerment. He worked as an Indonesia-wide Community-based Forest Management facilitator with DFID’s £25 million Multistakeholder Forestry Programme in Indonesia; and worked as Senior Campaigner for Environmental Justice with Friends of the Earth before co-founding LifeMosaic. Serge has directed most of LifeMosaic’s films.

What do you think are the greatest challenges facing indigenous peoples today?

Indigenous peoples are the stewards of much of the world’s biological, cultural and linguistic diversity. This diversity, much of it represented in indigenous peoples’ dynamic systems of traditional knowledge, is essential to human resilience in times of abrupt change.

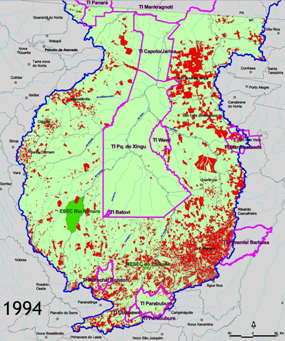

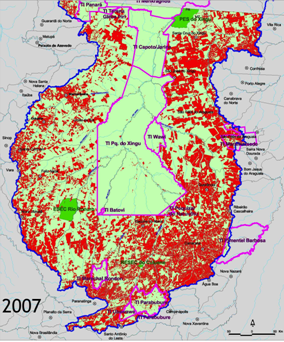

Communities with secure tenure rights are often the most effective managers and protectors of forests and other natural resources on their territories.

To illustrate this point, maps shown below from the Instituto Socioambiental (2009) show the headwaters of the Xingu river basin in the Brazilian Amazon in 1994 and again in 2007. The light green colour shows forest areas and the red depicts deforestation. The purple lines show the boundaries of the territory of the Xingu indigenous people.

Secure tenure rights for indigenous and local communities can also bring multiple benefits in terms of cultural resilience, food security, women’s rights, conflict avoidance, poverty alleviation, biodiversity, forest governance and climate security.

Yet many indigenous peoples across the tropics have no tenure rights, or their existing rights are not respected, and communities are excluded from decision-making around land. Between 2000 and 2010, an estimated 200 million hectares of large-scale land deals were concluded across Africa, Asia and Latin America. These deals are driven by increasing global demand, mainly for food, biofuels, and minerals.

Already today, in order to supply resource demand, large-scale developments such as logging, dams, mines, fossil fuel extraction, and plantations deny indigenous communities their lands, livelihoods and basic rights and destroy the ecosystems on which they depend. If demand for raw materials continues to rise on present trends, global resource extraction will triple by 2050.

The land rush is leading to: the squeezing of rural livelihoods and the loss of food security as communities are displaced from or lose access to resources and ecosystem services; increasing conflict, violence and human rights violations; disproportionate negative impacts on the poorest populations, and especially on women; large-scale conversion of natural ecosystems, with the destruction of forests and peatlands resulting in high emissions of greenhouse gases.

Many land deals take place on the lands and territories of indigenous communities, often without their prior knowledge, participation or consent. Many companies around the world use similar tactics to obtain land: inflated promises of services or jobs; community meeting attendance signatures used to prove consent to handing over land; threats and intimidation; the co-option and corruption of local leaders.

This land grabbing leads to: increased conflict, violence and human rights violations; disproportionate negative impacts on the poorest populations, especially women; squeezed rural livelihoods and a loss of food security as communities are forcibly displaced from, or lose access to their lands, forests and water.

Around the world indigenous peoples are suffering physical abuse, imprisonment, torture and death, especially where they try to assert their rights.

Indigenous peoples continue to suffer from high rates of poverty and human rights abuses. Although they represent around 5% of the Earth’s inhabitants, indigenous peoples constitute around one-third of the world’s extremely poor people. Their life expectancies are some 20 years lower than their non-indigenous counterparts.

In many places there is little accountability for governments and corporate interests that perpetrate abuses against indigenous peoples. These have little or no power or political voice and information about the impacts of proposed developments is often unavailable. A local inhabitant of Fife attending a recent LifeMosaic film screening said: ‘I knew this kind of thing happened in the Wild West, but I didn’t realise it was still happening today.’

Lack of access to relevant critical information limits community debates, planning, and action to protect their land and territories. Local human rights and environmental justice organisations often lack tools and information specifically developed for grass-roots facilitation.

LifeMosaic supports indigenous peoples to defend their rights, territories and cultures. We do this by producing popular education resources (often film) for indigenous communities, and by facilitating the widespread distribution of these resources, primarily to communities.

Projects are demand-driven, useful to a wide audience, and developed in partnership with communities, indigenous peoples organisations, and other movements for positive social and environmental change. The resources cover issues of particular relevance to indigenous communities such as the impacts of large-scale developments. To provide hope and inspiration the resources also show positive examples of community organisation; self- determined strategies for development; and the strengthening of cultural resilience.

What does your job at LifeMosaic entail?

LifeMosaic is a small organisation, so we all pitch in with everything, from making coffee to lighting the fire in the office (we’re based in Fife and it’s cold at the moment). On the programme side I help to facilitate and oversee all of the preparation that goes into our work, and I direct many of our films. Several times a year I visit communities myself, though not as often as I’d like to. I have a coordinating role, support LifeMosaic team members to develop their workplans, and help them to move forward on these. I am also responsible for major fundraising, though I am well supported in this by other colleagues.

Why is film such a useful tool of empowerment?

Film (or video) is not necessarily a tool for empowerment. Video can be used to manipulate opinion, sell you things you didn’t know you wanted, misrepresent peoples opinions, entertain, amuse, or inspire. Many advocacy videos try to convince of a certain point of view. Corporations use videos as a tool to convince indigenous peoples of the benefits of accepting their business proposition.

LifeMosaic mainly produces and distributes films as tools for empowerment. The films are primarily based on community testimonies; they present complex issues in an accessible and engaging way; and they support indigenous peoples right to free, prior and informed consent.

Our films often tell the stories of complex systems such as oil palm plantation expansion, climate change, or land rights. Instead of campaigning for a particular point of view, our films invite communities to critically analyse and discuss the issues, and to decide their own path.

In Anthropology we often discuss the contentiousness of representing indigenous people in a certain way. How does your organization navigate through the politics of representation?

While we cannot guarantee that LifeMosaic’s work always represents indigenous peoples as they would prefer to be represented, there are a number of ways in which we work to reduce the risk of misrepresenting indigenous peoples:

We always consult with indigenous communities and indigenous peoples organisations before deciding whether to develop a project and during project design. In this way, as far as possible we work on the basis of need. We almost always go to the field with local indigenous peoples organisations, who advise us on issues of representation.

We take FPIC (Free, Prior and Informed Consent) very seriously. Rather than seeing FPIC as purely the responsibility of companies and government, we regard FPIC to be at the heart of defining power relations. Communities must be able to refuse LifeMosaic’s presence if they do not wish us to film there. We hold meetings with communities and also discuss at length with individual interviewees. The process of requesting consent often involves ceremonies, where consent is not just asked of the community. At these times community shamans may also ask for consent for filming from the spirit world. It is only ever once full consent is given that we begin to use the camera.

As I write one of my colleagues is visiting a relatively remote community in Ecuador for 3 days without his camera in order to explain the work we are carrying out, and ask the community whether they consent to being filmed on a future trip.

There are many other safeguards that I will not cover here, but the most important one is that all is our primary audience are indigenous communities. We tend to hold several community screenings before we launch a film, and act on the recommendations that emerge. In this way we receive immediate and repeat feedback. This makes us very aware of, and hopefully careful, about representation.

Finally, I would say that we greatly respect indigenous peoples and indigenous communities, their resilience and their fortitude faced with human rights abuses and the destruction of the territories and resources. We work to provide communities with the basic building blocks of information to take their own decisions about large-scale land use changes.

Through your years of working in indigenous rights, can you describe one of your most memorable experiences?

It’s very difficult to choose! But I would say that visiting Songco, a village of the Talaandig tribe, in Mindanao, Philippines, is one of my most memorable experiences.

Two brothers, Datu Victorino Micketay Saway (Datu Vic), a customary leader of the Talaandig nation and previous leader of a national Philippines indigenous peoples organisation), and Waway Saway, an artist and a musician, after years spent away, both decide to return to Songco to focus on revitalising the culture of their tribe which was under threat from large-scale development, dominant religion, formal education systems, and economic systems.

As Salima, a young mother and artist, pointed out: There’s a lot of youth now, that are being influenced by another culture. They think that other cultures are much better than their culture, and that they can’t reach their dreams through sticking to their old culture. They believe that through that new culture they will reach their dreams.

Datu Vic worked with the elders to build a School of Living Traditions, a non-formal pre-school where Talaandig children learn about their culture by speaking in their own language, weaving, dancing, music, singing, story-telling, and playing traditional sports and games.

The School of Living Traditions became a model for cultural revitalisation that has now been extended to many other indigenous communities on Mindanao, with the full support of the Philippines Department of Education.

The Talaandig also set up Mothers for Peace a group of Talaandig elder women who host peace encounters between different sides (Marxist guerrillas, Islamic fighters, Government Military) of the armed conflicts that continue to plague Mindanao.

Waway Saway supported the young people to find a different outlet for their creativity by introducing them to painting, which had not been an artform in their area, using different clays from their ancestral territory for the colour of their paints. A few years ago the youth of Songco worked with the elders who recounted the cosmology and history of the tribe.

The youth painted this knowledge onto 1000 large canvases that they exhibited in the community.

The Talaandig also organised ‘cultural guards’, community members who act on behalf of the people to protect sacred sites, forests, and the wider territory. Another initiative they developed was work to protect their food and specifically seed sovereignty.

None of this work was supported externally. Instead in creative ways, the Talaandig demonstrated that there are other pathways to development, than becoming plantation labourers or mine workers, which is usually the only path that global markets seem to offer most communities. It was very inspiring, and transformed their self-esteem, and their vision of the future.

As Datu Vic said at the time: We can’t ask people to give us solutions to the problems we are facing today. Other people can probably help in trying to provide solutions, but the ultimate solution will come from our own selves.

In Indonesia, the Constitutional Court recently recognized that customary forests are not within state forests (ruling number 35). Have you seen any actual changes when it comes to indigenous rights and land tenure as a result of this change in legislation?

Until recently some 70% of the land area of Indonesia (130 million hectares) has been claimed by the Ministry of Forestry to be Indonesian State Forest Zone. Approximately 33,000 indigenous and local communities live within this contested area. To date, their tenure rights and forest management systems have not been recognised by the Indonesian government, despite many of them having managed their forests and territories under customary law for generations.

On 16th May 2013, the Indonesian Constitutional Court ruled that customary forests should not be part of the State Forest Zone, but forests subject to rights. This has the potential of validating the position of Indonesian Masyarakat Adat (which is often translated as indigenous peoples) that they are the owners of their lands, resources and territories.

Undoubtedly this ruling (known as MK 35) is a landmark decision in the struggle for indigenous peoples rights in Indonesia. The movements for the recognition of indigenous peoples rights has been energised by the decision, with communities across the archipelago erecting signs declaring their ownership of their customary forests. There is hope that this decision may be a step towards resolving the ever growing numbers of land conflicts that are erupting across the large contested area.

However analysis by Indonesian land rights experts shows that MK 35 does not guarantee the recognition of indigenous peoples’ rights to their lands, resources and territories, not least because to date there is no national legal mechanism to allow this recognition to take place. Despite advocacy by AMAN (the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Indonesian Archipelago) and many other civil society actors, to date there is little commitment or leadership by elites in the Indonesian parliament, government or other state institutions to move towards policies that would allow full recognition.

What advice would you give to a student who is wanting to work in indigenous rights?

Spend as much time as possible in communities, before you start to work in a setting detached from community realities. This can be more difficult to do, but it will serve you for many years to come. Have fun, and make friends. Later you will still have time to make colleagues. Be aware that today most jobs relating to indigenous peoples rights are quite rightly carried out by indigenous peoples. On the other hand, possibly for only a short time, there is a fair bit of funding out there at the moment, focused broadly on the relationship between community rights, forests, and climate change (not only from a forest carbon perspective!). Think of how you can build capacity in a real, unique and meaningful way.

Source: EcoPost

Categories

Latest news

- LifeMosaic’s latest film now available in 8 languages

- การเผชิญหน้ากับการสูญพันธุ์ และการปกป้องวิถีชีวิต (Thai)

- LANÇAMENTO DO FILME BRASIL : Enfrentando a Extinção, Defendendo a Vida

- Enfrentando la Extinción, Defendiendo la Vida (Español)

- Peluncuran video baru dalam Bahasa Indonesia : Menghadapi Kepunahan, Mempertahankan Kehidupan